NEW YORK (CNNMoney) — What happens if Congress fails to raise the debt ceiling by Aug. 2?

Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner says it would be “catastrophic.” A growing number of Republicans say that’s false — at worst it would be “disruptive,” in the words of Sen. Pat Toomey.

The reality is nobody really knows because it has never happened before: Congress has gone down to the wire in the past but has always raised the debt ceiling just in time.

“When I manage my family’s finances, I would not do something where the consequences are unknown and unknowable,” said Joe Minarik, who served as the chief economist of the White House Budget Office in the Clinton administration.

Likewise, he said, rolling the dice with the country’s financing terrifies him.

But that is what some lawmakers are willing to do if Congress can’t agree on a deal that serves as a significant down payment on debt reductionby Aug. 2.

If the ceiling isn’t raised by then, the Treasury Department won’t have enough money coming in to pay all the country’s bills and won’t be authorized to borrow to make up the difference. So that will mean delayed federal payments, Toomey said, but it won’t be default, as Geithner has claimed.

Debt ceiling: What you need to know

In Toomey’s opinion, the government can avoid default by continuing to pay interest and principal on outstanding debt. If investors get what’s owed them, they won’t blink if the country for a time can’t pay all its other legal obligations on time.

Even if Toomey is right, the reality would be a lot more difficult and complex than he makes it sound.

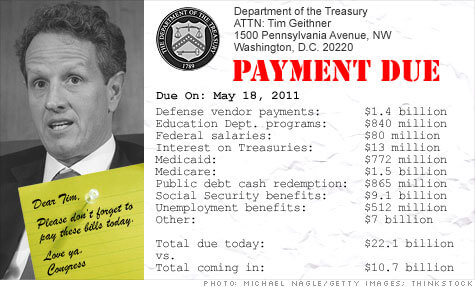

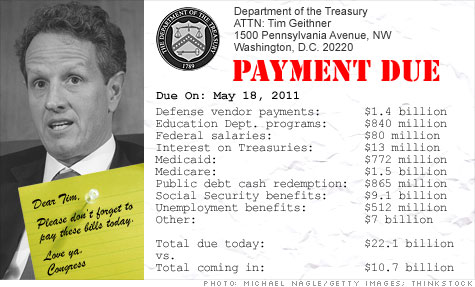

Daily cash crunch: It’s true Treasury collects enough in revenue overall to more than cover its interest and principal payments. The problem is that on any given day, that’s not necessarily the case.

“You don’t get paid in fiscal year 2011. You get paid on a Tuesday,” said Susan Irving, director of federal budget issues at the Government Accountability Office.

And some days, the Treasury will not be taking in as much as it has to pay out.

Deciding who gets paid: Many believe Geithner would have the authority to prioritize payments. So he could decide to pay bondholders first and then anyone else he thinks is most critical to pay without delay.

The law isn’t explicit about that, budget experts said. So it’s not entirely clear whether Geithner would be able to prioritize payments — unless Congress passes a law that says he does.

But even if he is allowed to prioritize payments, the situation could still be damaging.

Geithner: Risk default? You’ve got to be kidding

Deciding who to pay and who to put off will subject Geithner to a lot of second guessing from lawmakers and the public, and could open the door to lawsuits against the government. Those whose payments are delayed are likely to be quite unhappy and vocal about it.

And, “in a practical sense, the question is daunting,” said Minarik, senior vice president of the nonpartisan Committee for Economic Development.

That’s because most of the bills Treasury pays are essentially automated — whether they’re checks to contractors, taxpayers waiting for refunds, Social Security beneficiaries or federal workers.

And if interest and principal are to be paid first, everything else may have to be stopped until sufficient revenue comes in to take care of that. The same is true when Social Security checks have to be cut.

And there will be other headaches.

“There will be some challenge communicating to the entire government who will get paid and who won’t,” said Donald Marron, a former acting Congressional Budget Officer director.

Economic fallout: If a government check is late, someone’s cash flow will be hurt.

And that person or business, in turn, may spend less or delay paying bills.

Hopefully that’s all that happens.

The bigger worry is that at some point — no when can say when — investors or contractors who are still getting paid could start worrying that tomorrow they won’t be.

Or even if some investors remain confident, others may not be. And then everyone, whatever their beliefs, may start making decisions based on what the other guy is doing, which may include heading for the exit.

That doubt could drive up interest rates — and U.S. debt. That, in turn, will impair economic growth, which will reduce revenue and drive U.S. debt higher still.